(Image courtesy of Viz Comics.)

My recent blog post about the erstwhile practice of douching with Lysol prompted me to investigate other questionable customs that have fallen victim to the march of time and science. What follows is as astonishing glimpse at the lengths our forebears were willing to go in the name of progress, and a reminder that the more things have changed the more they remain the same.

Despite its backdrop of widespread famine, health crises and political upheaval, the century beginning in 1900 was welcomed as a brave new world in America and Western Europe. Rife with opportunity for social and self-improvement, for all its horrors the Industrial Revolution provided the ideal atmosphere in which to create new identities, fortunes and futures; progress was the order of the day, and entrepreneurs were as eager to supply products for personal transformation as consumers were to try them.

(Photo courtesy of Chicago History Museum.)

Thanks to breakthrough discoveries in chemistry and the invention of electricity, of particular interest were products with a scientific or technological bent, and—unsurprisingly, given the prevalence of cholera, tuberculosis and influenza—items that promised improved health (like corrosive antiseptics marketed as “intimate cleansers”) were embraced in the marketplace.

(Images courtesy of nymag.com)

Among the most egregious “advancements” of the early 20th century were products that appealed to vanity: radioactive skin tonics, arsenic wafers and mercury pills all purported to improve the complexion, promote vigor and recover youthful radiance.

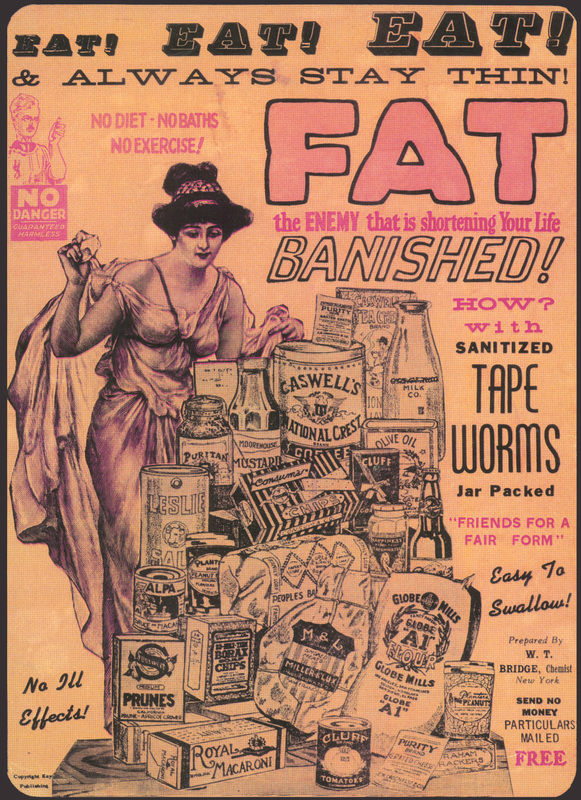

Another indicator of vitality was one’s physique. Local druggists were happy to transform sickly customers with weight gaining formulas loaded with sugar, oil and yeast, while portly men and women were routinely prescribed sterilized tapeworms to minimize their waistlines.

(Image courtesy of Science Photo Library.)

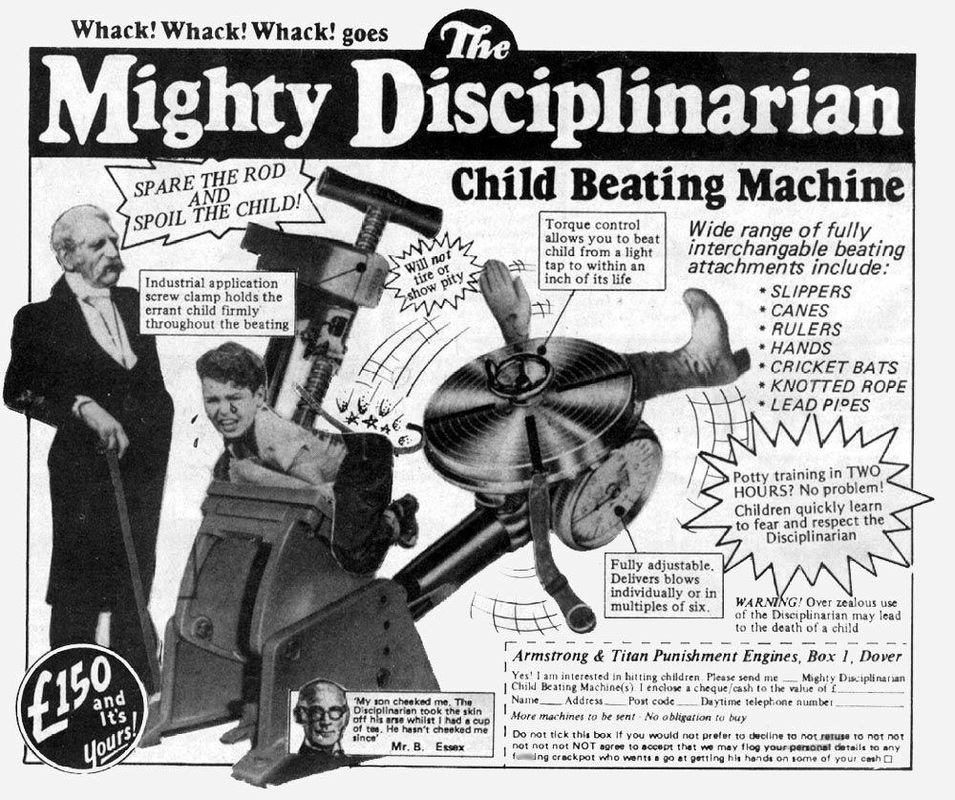

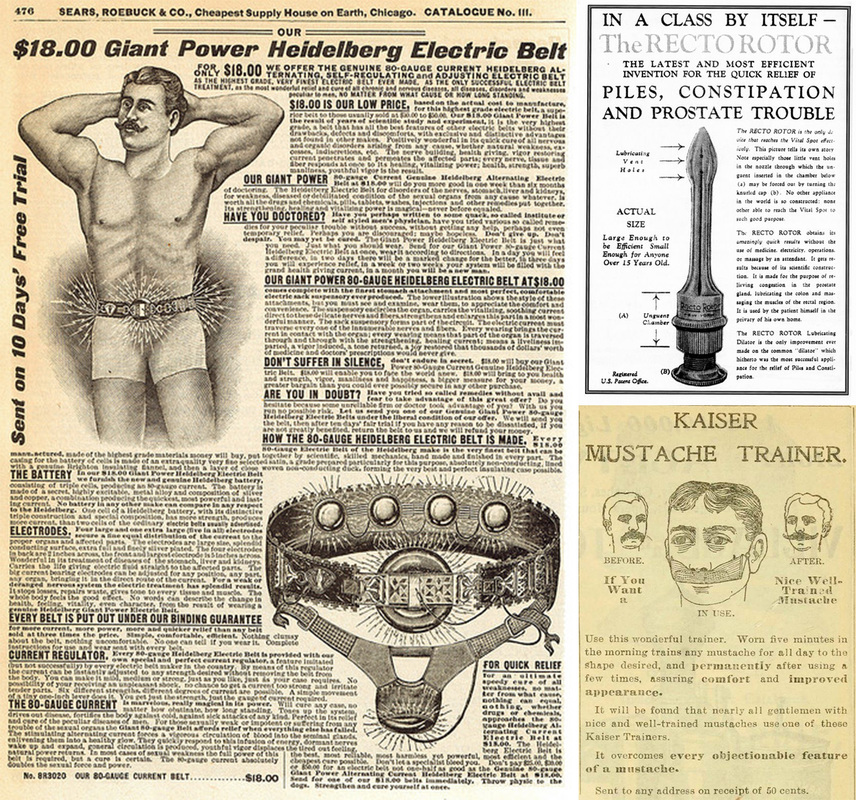

As its moniker suggested the Industrial Revolution was best known for its machinery, however, and mechanized contraptions appear to have been the era’s preferred answer to the question of life’s ailments.

“Male weaknesses” such as impotence, nervousness and infertility were addressed by electric belts that delivered shock waves to the groin. Facial harnesses promised to straighten crooked noses, firm sagging skin and train mustaches, while electric hairbrushes and magnetic hats supposedly stimulated hair growth, eased neuralgia and eliminated dandruff. A menacing device called the Recto Rotor dispatched with both gastrointestinal and prostate distress.

(Images courtesy of Mental Floss.)

But the potential dangers of these products pales in comparison to those created for children. Infants were routinely given cocaine, laudanum and heroin to soothe teething pains, irritability and sleeplessness; the inhalation of carbolic smoke—“a necessity in the nursery”—allegedly relieved a range of childhood ailments from bronchitis to asthma. Ads encouraged parents to spray concentrated insecticides directly on children and their food to control the spread of disease.

(Images courtesy of buzzfeed.com, pinterest.com and Ladies' Home Journal.)

And though we may collectively exhale sigh of relief in the disappearance of these products, how different are the modern practices of purposely injecting Botulinim toxin in one’s face or prescribing amphetamines like Adderall to hyperactive children?

Instead of smugly dismissing history’s blunders as primitive, we might be better served by using them as a reminder that “new” doesn’t necessarily mean “improved.” In fact, sometimes older is actually better (ahem, vintage clothing). But without the perspective that only time can provide, we may find ourselves rushing to achieve progress only to end up back where we started.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed