(Ad excerpt courtesy of vintageadbrowser.com)

I might be the only person who would delight in its discovery, but the truth is I squealed when I uncovered it. There it was, in an old cardboard box in a neglected corner of my mother’s garage: my grandmother’s 1930s douche.

Was my Irish Catholic and often humorless grandmother that obsessed with cleanliness, or did she like so many women use it as (gasp!) birth control?

Warning: this post acknowledges the existence of sex and women's reproduction.

Now's the time to turn back if you can't bear to read the word "douche" used as a verb.

Moral disagreements about its practice aside, birth control has been around since the beginning of recorded history. Remarkably, the extract of acacia leaves—whose use was first documented in Egyptian papyrus dating to 1850 BC—contains a spermicide so effective that it is still used in modern contraceptive jellies. And with the exception of the Middle Ages, when plague threatened population stability (and the Inquisition threatened its users), birth control was practiced largely without incident until the 19th century.

(Image courtesy of Chrysalis Archaeology)

But the population explosion incited by the Industrial Revolution turned pregnancy prevention into a matter of public health. Overcrowded cities bred disease and competition for resources threatened quality of life; this coincided with the advent of the feminist movement in Western Europe and America, which advocated more active roles for women in family planning. In early 20th century Britain, this led to the acceptance of contraception for the wellness of its population, though always within the confines of marriage…and in typically English fashion, never discussed openly.

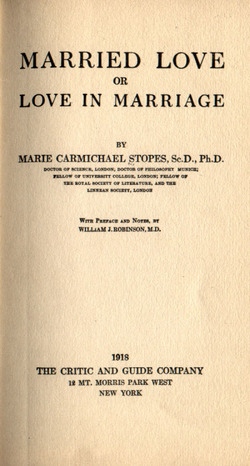

British feminist Dr. Marie Stopes wrote a controversial book entitled "Married Love" in 1918. In it, she included information about female sexual desire, menstruation and birth control and argued that marriage should be an equal relationship between both partners.

In its sixth printing within two weeks of its release, "Married Love" sold three quarters of a million copies in the UK by 1931. Though officially banned in the United States until the same year, a survey of American academics cited it as one of the 25 most influential books of the previous 50 years in 1935.

For all her progressiveness, however, Dr. Stopes's (and her American counterpart, Margaret Sanger's) motives for advocating birth control were not entirely altruistic: both also advocated the use of birth control as a form of eugenics among the poorer classes.

(Image courtesy of Wikipedia)

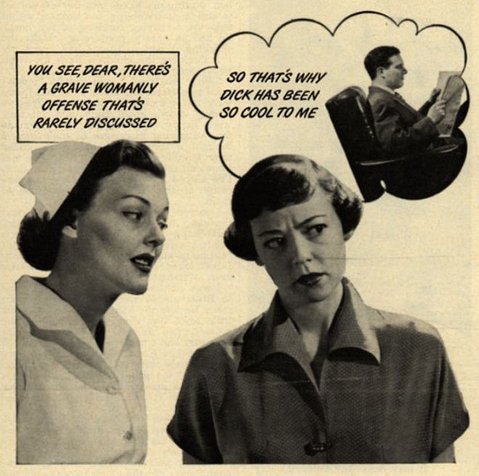

The Act, which remained law until 1965 for married couples and 1972 for singles, had predictably disastrous consequences. Leveraged and enforced by the US Postal Service, handwritten letters that included the word "sex" were confiscated and their senders arrested; medical students were unable to receive anatomy textbooks delivered by US Mail; countless works of art and literature were banned for supposedly lewd content.

detaining an artist whose painting of a fully submerged woman suggested nudity and was therefore obscene.

(Image courtesy of Case Western Reserve University)

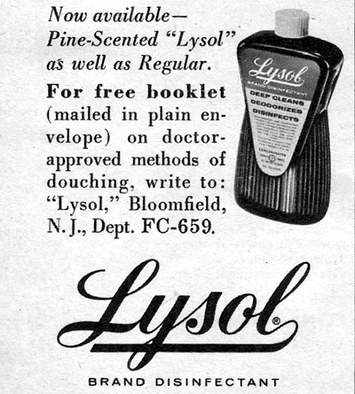

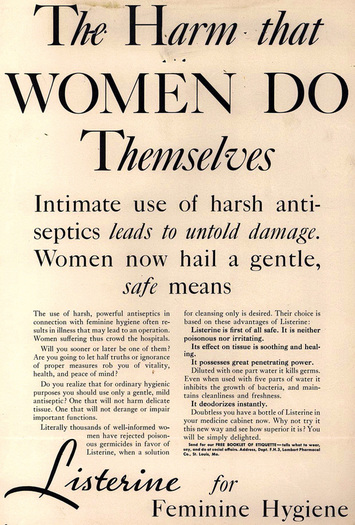

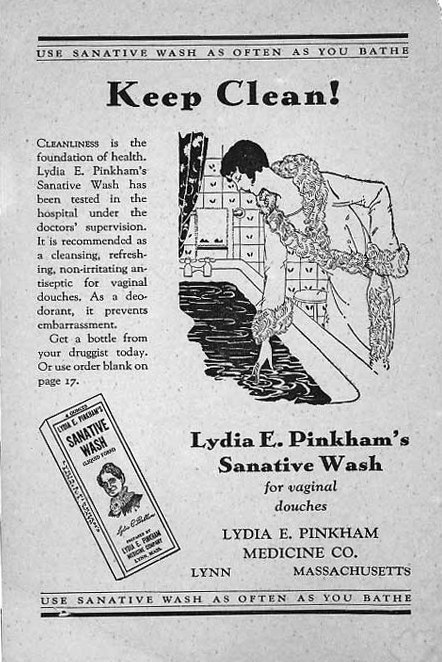

Sadly, the makers of early mass-marketed douches applied the term “hygiene” quite literally, as the most popular products were made by Lysol. Yes, that Lysol. Unsurprisingly, while they worked wonders on a kitchen floor, Lysol and its competitors Zonite and Listerine were not only overwhelmingly ineffective at preventing pregnancy but seriously threatened women’s health. Furthermore, their antiseptic branding stigmatized female reproduction as unclean and perpetuated sales of douches to maintain “dainty feminine allure” long after their contraceptive properties were disproved.

Advertisements from the 1920s to the 1950s heavily promoted the "hygenic" benefits of douching with germicides.

(Images courtesy of collectorsweekly.com and mum.org)

Which brings me back to my Nana. Her fastidiousness (she regularly washed her walls with soap and water) leads me to believe she would have considered a Lysol douche perfectly reasonable, whether for personal hygiene or contraception. I’m only shocked that she and thousands of other women didn’t end up sterilizing themselves along with the kitchen floor.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed