(Image courtesy of Maly Photo Archives.)

My mind immediately went to the hours my sister and I played with Barbies as children. At 1/6 the scale of human clothes, Barbie’s enviable wardrobe would be perfectly sized to use as ornaments, and a vintage Barbie herself could substitute as the treetop angel.

Despite my sister’s and my constant ribbing of her as a highly-functioning hoarder, my mother is actually a “collector’s Collector,” one of those people who has somehow saved all the right things and knows exactly where they are. Barbie and her clothes were no exception, and I soon returned home with three suitcases of perfectly-preserved vintage Barbie clothes I hadn’t seen in over 30 years.

(Image courtesy of Black Cat Vintage.)

I had forgotten what I had, and opening the cases was like re-living every Christmas morning of my childhood. Like a scene out of Toy Story, hundreds of outfits in every color and style begged to be loved after three decades in storage.

As I sorted them into ensembles I was astounded to notice the same minute details that are the cornerstone of vintage dressmaking and so familiar in my work. I would certainly have been too young to appreciate such craftsmanship when I played with them, but had the quality of these garments—reinforced by the jewels in my mother’s closet—inspired me to pursue fine fashion as a career? Quite possibly so.

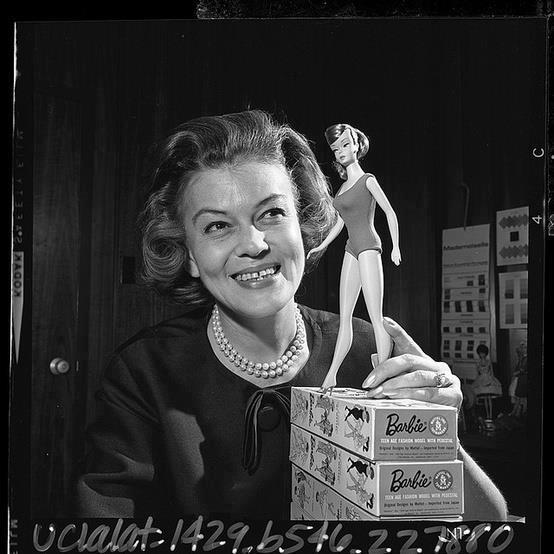

Turns out, though Barbie was introduced in 1959, it took three years of research, design and development to bring her to fruition. An entire year of that research was devoted to her wardrobe, the proper execution of which, Mattel reasoned, could catalyze revenue long after the original $3 doll was purchased. Charlotte Johnson, a 20+ year veteran of the garment industry, was tasked with the job.

(Photo courtesy of barbielistholland.)

Mattel chose to manufacture the dolls in Japan, where workers were more familiar with the materials and processes required to make Barbie soft, pliable and life-like. To boost efficiency, Barbie’s clothes could also be manufactured in Japan, where legions of “homework people” (seamstresses who worked at home) would sew the doll’s clothes for little money.

In 1957, Charlotte Johnson was dispatched to Tokyo where she worked with a Japanese designer and two principal seamstresses six days a week for a full year. Multiple versions of Barbie’s original eight outfits were produced, but none met Johnson’s rigorous standards until Japanese manufacturers fabricated custom components like micro-printed fabric, 1/8” zippers and 1/16” buttons, all of which were then hand sewn onto Barbie’s clothes. Barbie’s sales were so impressive after the first year that Johnson also began attending the Paris couture shows so she could mimic the designs of Christian Dior and Yves Saint Laurent.

Note Barbie's version has a hem!

(Images courtesy of (l to r) Black Cat Vintage and Wikimedia Commons.)

(Image courtesy of Black Cat Vintage.)

(Image courtesy of Black Cat Vintage.)

(Image courtesy of Black Cat Vintage.)

The fact that the same changes occurred in human fashion is only more evidence of how Barbie has changed with the times. But how many children have those changes deprived of the opportunity to experience something exquisite, even if only through a toy? Can we blame people for looking like slobs if they were never exposed to another option, even on a much smaller and more accessible scale?

(Image courtesy of Black Cat Vintage.)

Thank you Charlotte Johnson.

The Rosson House Museum until December 31, 2017.

(Image courtesy of Black Cat Vintage.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed