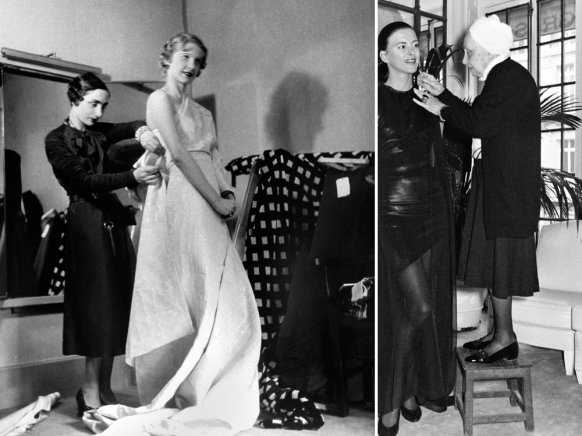

(Photo courtesy of Sothebys.com.)

(Photo courtesy of Picture-Alliance: Boris Lipnitzi/Roger Viollet.)

I began to question my logic when Lot 8, a Dior suit almost twenty years younger than the 1971 Grès, sold for 28,000 euros, over 15 times its estimated value. Only moments earlier Lot 6, a plain black Balenciaga suit, sold for quadruple its estimated price to no less than the Louvre’s famed Musée des Arts Decoratifs. So much for the theory that museums might not get funds released in time to bid. Was there any chance bidders might suffer fatigue (as it appeared doubtful they would run out of money) by Lot 119, “my” Grès?

(Photo courtesy of Sothebys.com.)

When Lot 119 went on the block I broke out in a cold sweat. I registered my interest with an early bid, which was quickly overtaken by two more from opposite sides of the packed room. I raised again and was overtaken by one of the same bidders; I raised again. By then the auctioneer knew she had hooked us both and, like a beautiful ingénue with two suitors, played us off each other.

“I wonder,” said the auctioneer in French, “who will it belong to?” With that, my competition outbid me once more.

For what seemed like ten minutes (but was actually more like 30 seconds), a tennis match ensued with the auctioneer’s chin bouncing back and forth from me to my rival, each of us raising the other until it became clear that unlike me, my competitor had no budget. Whatever I bid, she would simply bid more. As much as I longed to own the gown (and let’s face it, to beat her), I was only a few bids away from risking a sum that could sink me if she conceded. The next time the auctioneer’s chin bounced my way, I refused. The look of surprise on the auctioneer’s face reminded me of a woman whose date excuses himself and ditches her with the dinner tab. I swore the words, “Going once, going twice…” were said in slow motion just to prolong my agony, but by the time the gavel struck I knew my “baby” was gone.

When the final lot was sold, Didier Ludot’s collection of 171 pieces fetched nearly 1 million euros, over 100,000 of which was spent by a single bidder buying clothes for his new fiancée. (Barf.) A British bride-to-be purchased a Lesage-embroidered Balmain to wear to her mountaintop wedding for a cool 18,750 euros. (I hate her.) But the most staggering purchase was a 1965 angel pink Balenciaga smothered with ostrich feathers. It belonged to Francine Weisweiller, a Paris socialite and personal friend of Jean Cocteau, and sold for over 56,000 euros.

Proof that the auction of a lifetime includes prices to match, and that—even at Sotheby’s—auctions are more of a blood sport than their elegant veneers suggest. To their credit, however, the audiences still clap at a particularly impressive score. Just like they did at the Coliseum in Rome…

(Photo courtesy of Sothebys.com.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed