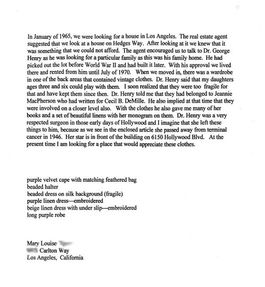

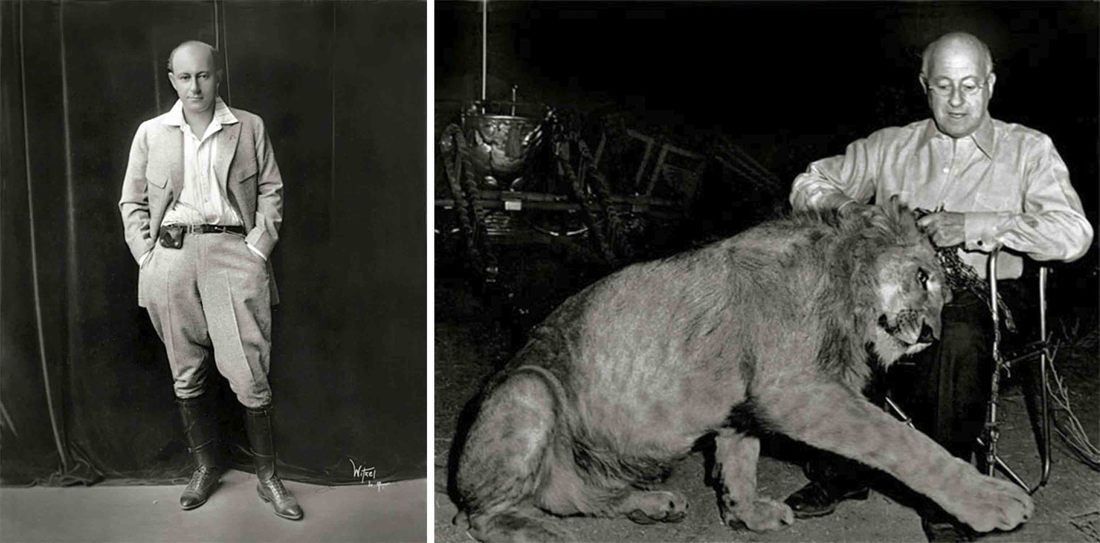

(Image courtesy of Cecil B. DeMille Foundation.)

For over 20 years I have had the pleasure of working with priceless fashion artifacts from the archives of movie stars, historical figures and illustrious designers. You might be tempted to think that no clothing acquisition, restoration or discovery could phase me after so long, but you would be wrong. There are still garments that unglue me, either with their provenance, their artistry or their origin.

Recently I found a piece with all three of these virtues … in a garbage bag headed for the landfill.

Time and time again, priceless artifacts turn up in Goodwill shops, estate sales and theater costume departments after being donated by the overwhelmed children of such pack rats. These finds are the Holy Grail for vintage collectors, and their lure justifies the often unglamorous work that might lead to their discovery.

(Video courtesy of What Sells Best News.)

One afternoon, a local theater was disposing of donated items it could no longer use and thought I might be interested in acquiring them for scrap. I accepted and returned to my studio with several plastic garbage bags full of what I assumed would be deteriorated clothing from which I might salvage beads, buttons and zippers for use in future clothing restorations.

Out of one particularly heavy bag floated hundreds of ostrich feathers, which are typically a sure indication of 1920s garments. I was correct: the bag was filled with Jazz Age clothing, much of it beaded, accounting for the bag’s weight. I expected most of the miniscule seed beads to be loose in the bottom of the bag, so I unpacked it fully; but instead of beads I found a typewritten letter at the very bottom.

The letter’s author recounted having moved into a rented Hollywood Hills home in 1965. Inside the home she found a wardrobe that contained vintage clothes, which her new landlord, a physician, said she could keep for her daughters to play with.

“I soon realized,” she wrote, “that [the clothes] were too fragile … and have kept them since then. At the present time I am looking for a place that would appreciate [them].”

(Scan courtesy of Black Cat Vintage.)

Though Jeanie MacPherson may not be a household name, Cecil B. DeMille most certainly is. The founder of Paramount Pictures and the most successful producer/director in movie history, DeMille is remembered as much for his autocratic personality as for his cinematic showmanship. Though his films comprise the canon of American cinema, his temperament famously alienated many with whom he collaborated, from actors to business partners to, at times, his own wife.

(Images courtesy of Cecil B. DeMille Foundation.)

That such a idiosyncratic director should have chosen an unknown female screenwriter to articulate his vision beginning in 1915 seems incongruous…until you learn more about Jeanie MacPherson.

The daughter of wealthy parents, Abbie Jean “Jeanie” MacPherson (like DeMille) was born in Massachusetts and drawn to the stage in her youth, acting, dancing and singing until she discovered motion pictures in her early twenties and decided to become a movie star. Credited with 146 acting roles between 1908 and 1917, she got her first opportunity to write as the result of an accident at Universal Pictures in 1913: the only film negative of a movie in which she had appeared was destroyed, and she was asked to reshoot the entire motion picture exactly as she recalled it because the original director was unavailable. MacPherson then wrote, directed and starred in The Tarantula at age 27, making her the youngest director in motion picture history.

(Image courtesy of Women Film Pioneers Project at Columbia Univ.)

Unsurprisingly, DeMille refused and a power struggle ensued with MacPherson emerging the unlikely victor. The incident was memorable enough that when MacPherson terminated her contract with Universal and approached DeMille for work in 1915, he hired her immediately, first as a stenographer and then as a screenwriter.

(Images courtesy of IMDB.)

The collaboration was a productive one, with MacPherson writing 30 of DeMille’s next 34 films including Carmen, Joan the Woman, The Ten Commandments and Adam’s Rib. By the mid-1920s, Jeanie MacPherson had not only given a voice to women in the emerging film industry, she became a founding member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences and the highest paid employee in DeMille’s scenario department, earning $1000 a week (equivalent to $14,000 a week today).

Given MacPherson’s remarkable charisma and even more impressive salary, I assumed the bag before me would contain clothing like the world had rarely seen. What I found was life changing.

Join me next month to discover what it was.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed